We should all heed the wisdom of the dead. Their hindsight is our foresight, helping is to see far beyond the little valley of our own life. The piece of advice that every really wise dead person offers us is this:

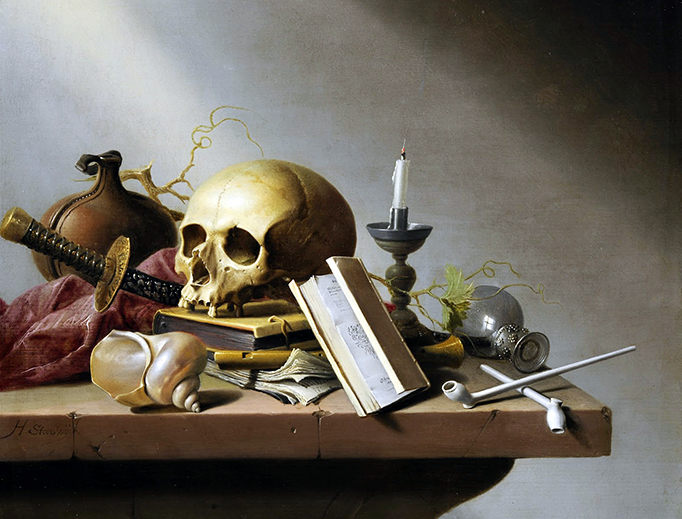

Memento mori. “Remember your death.” After all, it’s unavoidable. That doesn’t mean we should think endlessly about death, but we ought to live in close company with the fact that at some point our life will be folded up and borne away. This habitual perspective makes a profound difference.

Before you click the little red “x” in the corner, let me try to justify saying this. There are at least three good reasons for remembering your death: number one, this perspective will keep you from wasting your time; number two, it will keep you from anxiety; number three and it will prepare you for success.

1. To remember your death frees you from wasting time.

One of Stephen Covey’s “7 Habits of Highly Effective People” is to “begin with the end in mind.” Until we know what our goal is, we can’t know what progress is. But what is the goal, anyway?

In fourth grade I realized I was in school because I had to get to high school, where I would go because I had to get into a good college, which I needed to landing a high paying job, which I needed to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that I was marriage material. Then would come the house, the cars, the better job, the more stuff, the promotion, the boat, the jet, the still better job, international acclaim, honorary degrees and then — my demise, when all my work and sparkly stuff would be completely and utterly useless to me. It was as though Jesus had spoken the parable to me: “[The rich man said to himself,] Soul, you have ample goods laid up for many years; relax, eat, drink, be merry.’ But God said to him, ‘You fool! This very night your life is being demanded of you. And the things you have prepared, whose will they be?’ (Luke 12:20)

There it is: the memento mori. It keeps us from the frenzied pursuit of unworthy goods and helps us remember that time – our most precious commodity – is limited, so we’ll avoid wasting it or putting necessary things off.

And honestly, it’s very easy to procrastinate when it comes to preparing for death. Most of us put our death off daily. It’s human to avoid certain things because we think that in the magical future they will come easier for us, or we’ll simply wake up to find ourselves doing those things – some day. In the sage words of John Fogerty, “’Some day’ never comes.”

Remembering death rids us of the idea that we’re waiting for something to happen and initiate us into “reality.” You are too important to live in a holding pattern, waiting for this degree, this job, this relationship, this success, to legitimize your existence.

2. To remember your death frees you from anxieties about success and failure

Everyone struggles to gain this amorphous thing called “success,” but what is it? Whatever else we might say, it’s clear that in the light of our life’s eventual closure even what seems to be a momentous failure isn’t worth our anxiety. From the perspective of the Last Things, every failure is at worst a minor setback and at best a great help. (Any happily married couple will acknowledge that the failure of a previous relationship led to the success of their current one.) This also means that every success, however magnificent, has only relative value and shouldn’t be a cause for obsession. Peace rushes into the vacuum left by anxiety and obsession.

Although the word “success” suggests different things to different people, it’s possible to speak of a “successful human being” in a totally objective sense. The truth is that we are all – all – created for one goal, one telos, one end.

3. To remember your death allows you to avoid the one real failure and to achieve the one real success.

Like Martha from the Gospels, we are distracted and busy with many things. Like her sister Mary, we must hear Christ saying to us “One thing is necessary.”

Life throws everything at you all at once and says “Catch!” We’re all stretched uncomfortably by work, duties to our families, worldwide pandemics, ballot counts, and the thousand other little things that fill a life. As important as these things may be, many times they’re just a distraction from the one thing that really matters.

And there is only One that really matters.

Consequently, there is really only one failure. The French novelist Leon Bloy captured it in a succinct phrase which has gained popularity in recent years: “The only real sadness, the only real failure, the only great tragedy in life, is not to become a saint.” Remembering that each of our lives ends in death makes us evaluate everything against the one goal of becoming a saint. Ultimately, that is the true criterion of success.

What does success look like? It’s conformity to the person of Jesus Christ. He is the fullness of the Father’s revelation to us and he reveals us to ourselves. Who God is and who He made us to be are all made present in him.

4. Three borrowed lines to get us going

If you follow the argument, what may have seemed at first to be an unhealthy fascination with death actually turns out to be, quite literally, the most practical concern. Remembering our death is the key to not sweating the small stuff, to recognizing what has real value and is worth pursuing, being at peace with oneself and with the world. The memento mori gives us the full view of our life’s landscape, in our little valley and beyond it. If, to borrow a line from Socrates, “The unexamined life is not worth living,” then only someone with a lively sense of his coming death can have a life worth living.

Contemplating our mortality helps us to recognize the necessity of beginning our preparations not “some day,” but “today.” The time we have for achieving sanctity is limited, and it’s the most difficult thing conceivable. But to borrow a line from the ever-insightful Patrick Coffin, “What else is there?”

Frankly, there are lots of things. Sparkly things. Soft and comfortable things. But to borrow a line from Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI, “The world offers you comfort, but you were not made for comfort. You were made for greatness.”

Leave a Reply